Replace “E” with “A” to Truly Understand Business Profitability

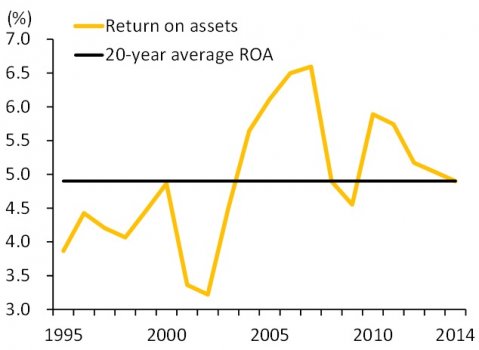

If a company can generate a good net profit relative to the assets it invests in, its return on assets (ROA) is strong. ROA is a measurement that matches the way a manager thinks about business – What assets do I need? What do I get in return? The decision of how to pay for those assets is almost irrelevant when it comes to creating long-term value. ROA’s major weakness is that it is industry specific, but for those with access to data, this should not be a problem. ROA across the world is now hovering near its long-term average of 5%.

ROA is a Simple Way to Measure the Profitability of Your Business

ROA is the measure I use to understand the profitability of a business. Calculated as a business’s annual net profit, divided by the average assets that were in place throughout that year. Higher is better.

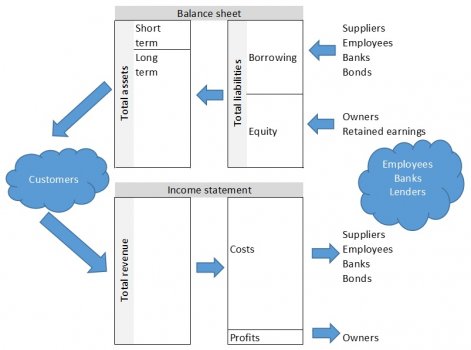

How Business Works: Invest in Assets, Make Profit

Business is simple – you invest in assets (think old-school physical assets or new-school employees and their computers as assets) and try your best to generate revenue from those assets. Eventually, you generate revenue levels that exceed the cost of running your business, hence generating profit. The beauty of using ROA as a measure of profitability is that it perfectly matches the way business works. In addition, it disregards how you actually paid for those assets (from investor equity or bank loans).

The Value of a Business comes from its Assets, Not how They Were Paid for

The Value of a Business comes from its Assets, Not how They Were Paid for

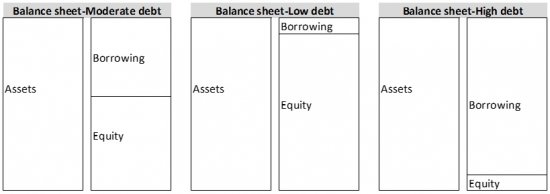

Nobel Memorial Prize winners Modigliani and Miller in 1958 (and revised in 1963) showed that the way you finance a company has little impact on the value of that company. There is a small gain from borrowing thanks to the tax deductibility of interest payments, but that gain is offset as debt levels reach distressed levels. In terms of the total value of the business, it comes from the assets of the business, not from the way a company finances those assets. This finding is reminiscent of the story of the guy who, when asked how he wanted his pizza sliced replied, “Better make it six pieces. I could never eat eight.” Messing around with how a company is financed (see the three examples below) is not what a manager should be thinking much about.

Adding Profitable Assets is the Business of Business

From a business owner’s perspective, value comes from making a careful investment in assets-investments that generate a good net profit (revenue minus costs). Adding profitable assets to a business is the business of business. When management succeeds at this, ROA will be high and/or rising. ROA allows an investor to understand how a management team is doing with regard to adding profitable assets. The measure has one major weakness for the average investor – it is not as easily comparable between random companies. You usually need to consider a company relative to peers, but since I always consider this in my advisory business, the measure is suitable for my style of investing.

ROA has Been Hovering at its Long-Term Average of 5%

Over the past 12 years, ROA of companies across the world (including nearly 8,000 companies globally) has averaged about 5%, hitting a 6.6% peak in 2007, and a 3.2% low in 2002. Over the past three years, ROA has leveled out to the long-term average of 5%.

Do you use ROA or ROE? Why do you prefer one over the other? I would love to hear your thoughts! Any comments or question you might have, I would like to know. Is anything unclear? Please let me know in a comment below.

References:

Modigliani, F.; Miller, M. (1958). The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment. American Economic Review 48 (3): 261-297.

Modigliani, F.; Miller, M. (1963). Corporate income taxes and the cost of capital: a correction. American Economic Review 53 (3): 433-443. JSTOR 1809167

DISCLAIMER: This content is for information purposes only. It is not intended to be investment advice. Readers should not consider statements made by the author(s) as formal recommendations and should consult their financial advisor before making any investment decisions. While the information provided is believed to be accurate, it may include errors or inaccuracies. The author(s) cannot be held liable for any actions taken as a result of reading this article.

Originally published on May 13, 2015 at: www.equities.com.