The 10 Best Days Is Not a Myth

Watch the video with Andrew Stotz or read the research below.

Behavioral economics teaches us that our emotions play a major part in our trading.

First of all, A. Stotz academic-style research starts with us asking a question. Then we use previously conducted research to understand what we already know about our area of inquiry.

We formulate a hypothesis to test from that, and select a data set, such as “U.S.” or “Emerging Markets”. We clean that data set as minimally as we can while still removing outliers that don’t really represent it.

Once our underlying data is ready, we apply methodology: “Here’s how we’re going to calculate and test this hypothesis.” Then we analyze the results.

From a practical perspective, we want to know, “How can this help us? What recommendations for action can we take from this, what can we learn from this to apply to our investing?”

Question

Here’s one question we had: “What would the impact on terminal wealth be if an investor missed the 10 best-return days in the U.S. market over a 10-year period?” We hypothesized that missing just these 10 days would have a significant negative effect on overall return.

Review

We looked at Seyhun’s 2003 paper. He calculated US returns over a long (1926-1993) and a medium-term (1963-1993) period of time. He found: missing the 12 best months reduced terminal wealth by 86%; missing the 10 best days reduced terminal wealth by 38%; and missing the 10 worst days increased return by 92%.

Trying and failing to time the market is what is most likely to happen to investors, and when that happens, it hurts returns massively.

In 2004, Johnson & Krueger did a study of dollar-cost averaging and market timing. Using daily returns of the S&P 500 from 1982-2001, they found that missing the 10-50 best days decreases annual returns by 24%-80%, and missing the combination of both the best and the worst days increases annual return by about 15%.

We’re not trying to think about “What trading strategy could do this?” because it would be extremely hard to figure out. The key point is that we should not be trading in and out of the market. So avoid market timing. Dollar-cost averaging can help do just that.

In 2009, Estrada found that from 1900-2006, missing the 10 best days would have resulted in a 65% lower portfolio value, and missing the 10 worst days would have resulted in a 206% higher portfolio value.

Again, the odds are stacked massively against your timing it right, because 10 days out of the period from 1900 to 2006 account for a minuscule 0.03% of total days.

Estrada then looked at 16 emerging markets and 110,000 daily returns. He found that missing the 10 best days would result in a 69% lower portfolio value and missing the 10 worst days would result in a 337% higher value; these extreme values are due to emerging markets being so much more volatile than developed markets such as those in the U.S.

Once more, it would be extraordinarily difficult to get the ideal timing right, because 10 days out of 110,000 are only about 0.15% of total days.

In 2011, Faber looked at S&P 500 returns from 1928 to 2010 and saw that extreme days had the same impact. He found that 60%-80% of the best and worst days occurred in declining markets, which he defined as markets that were below their 200-day simple moving average.

His research suggested that investors can time the market to some extent by being out of declining markets. So I think that insomuch as you can accurately gauge momentum turning against the market and against you, being out of it at that time could be beneficial.

Hypothesis

Let’s go to our hypothesis: Missing the 10 best days would significantly lower terminal wealth over a 10-year time horizon.

Data

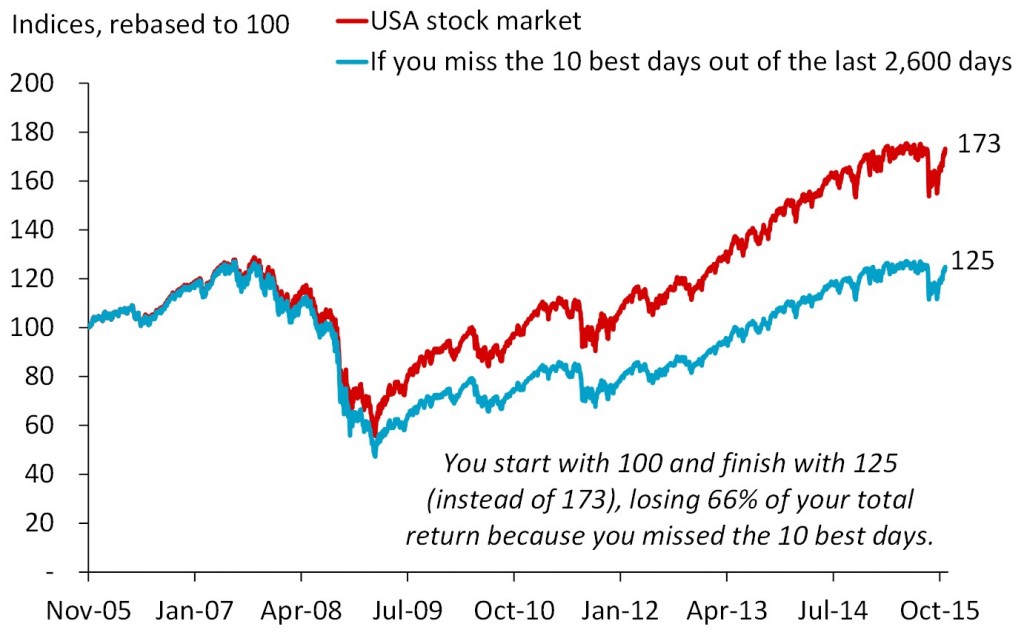

We looked at data for the last 10 years in the US (about 2,600 trading days).

Method

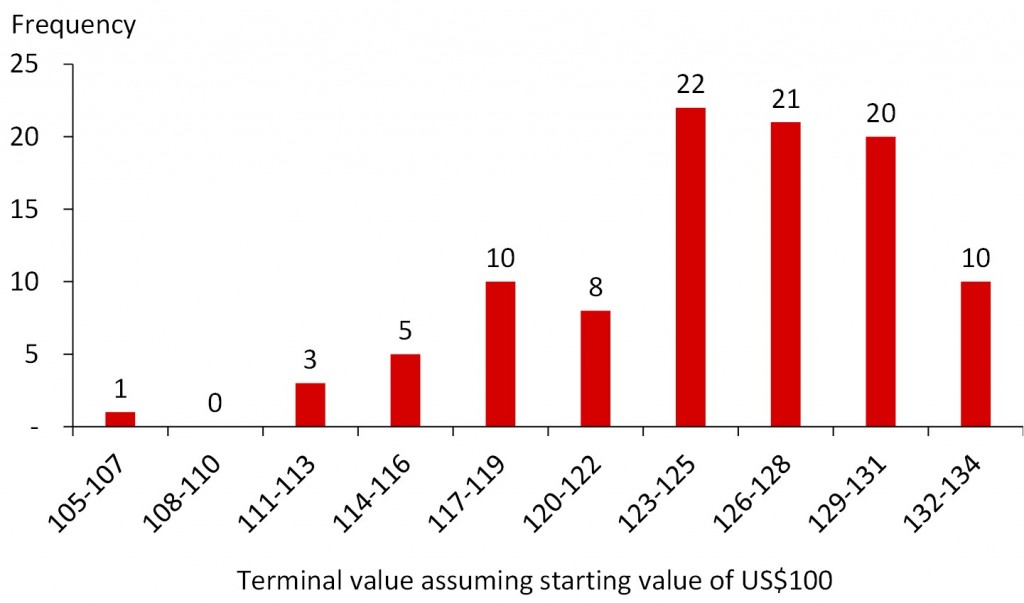

We calculated daily percentage change. We identified the 100 best and 100 worst daily returns, and then we invested in the market, but removed 10 randomly selected days, resulting in a 0% return for those days. We repeated this process 100 times.

So: “What would happen if you missed the 10 best days?”

The probability of you actually being out of the market on the exact 10 best or worst days is highly unlikely, which is why we chose our 10-day sets randomly.

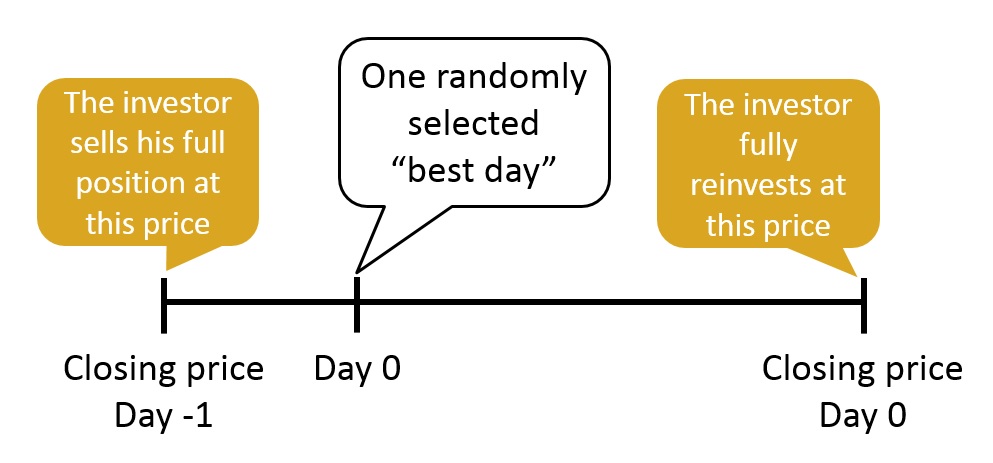

Let’s look at exactly how we executed our hypothetical trading day on the 10 days we were out of the market. We’ll call one of those random days “Day Zero”.

We sold our full portfolio position just before Day Zero. And then, right after it, reinvested at the closing price. So we missed that day entirely.

Results

Here is what we found. The blue line labelled “125” shows returns that are missing the 10 best days out of the total 2,600 in the measured time period.

We can see the distribution and the frequency in the different ranges. Most total returns ended up between 123 to 125, 126 to 128, and 129 to 131, as represented by the three highest bars.

Action

- Missing the 10 best days during 10 years seriously hurts your terminal wealth

- On average, you would lose 66% of your gains, but you can lose as much as 75%

- The best strategy is also the simplest strategy: Stay invested so you don’t miss the 10 best days

Learn more about how likely it is that an investor would actually miss The 10 Best Days, in our post: Clustering of Best and Worst Days or what impact missing The 10 Worst days has on your terminal wealth.

Do you buy and hold or do you try to time the market? What do you think about our academic-style research? Any comments or questions? Is anything unclear? What would you add to the post? We’d love to hear from you in a comment below.

Feel free to share this article with your friends.

DISCLAIMER: This content is for information purposes only. It is not intended to be investment advice. Readers should not consider statements made by the author(s) as formal recommendations and should consult their financial advisor before making any investment decisions. While the information provided is believed to be accurate, it may include errors or inaccuracies. The author(s) cannot be held liable for any actions taken as a result of reading this article.