VMC: Mistake #4 – Confusing Growth Capex with Maintenance Capex

This post was originally published here.

The top #4 valuation mistake takes us into a discussion about confusing growth Capex with maintenance Capex. Many analysts miss the relationship between Capex, depreciation, and sustainable growth. Which is why we’ll review these aspects within this chapter.

First though, a quick recap of the full list of Top 9 Mistakes.

The Top 9 Valuation Mistakes

- Overly optimistic revenue forecasts

- Underestimating expenses causing unrealistic profit forecasts

- Growing fixed assets slower than revenue

- Confusing growth with maintenance Capex

- Forecasting drastic changes in cash conversion cycle

- Underestimating working capital investment

- Valuing a stock using the calculated Beta

- Choosing an unreasonable cost of equity

- Not properly fading the return on invested capital

What is Capex?

Capex stands for capital expenditure. It is the money spent acquiring fixed assets or repairing or upgrading existing assets. Of course, Capex is a long-term investment item.

If you bought a can of oil to work for a piece of capital equipment, it might be something that is necessary to keep the machine running, but it’s not a long-term addition to that asset. But if you build an extension onto a production line, then that is considered ‘upgrading an existing asset’ as it’s a long-term upgrade.

Because fixed assets last longer than one year, the Capex cost is not fully charged as an expense in the year that’s it’s paid or incurred. So, Capex is capitalized over the life of the asset. This appears as an annual depreciation charge in the P&L which accumulates on the balance sheet.

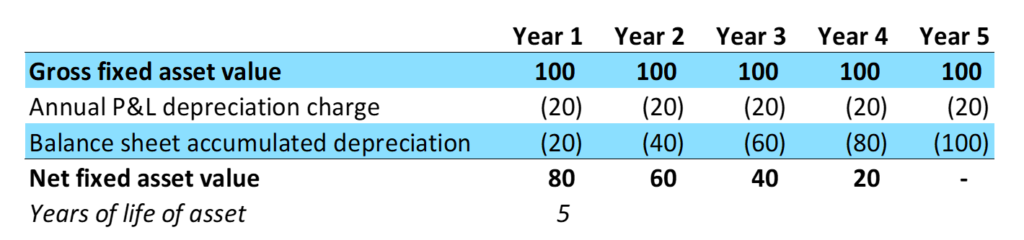

Let’s consider an example of a company that buys a 100-dollar asset with an estimated lifespan of five years (see Fig. 1). The gross value of that asset never changes; it’s one hundred dollars. That’s what you bought it for.

We can arrive at the annual P&L depreciation charge by taking $100 divided by 5 years and saying, “Every year, this is going to depreciate by $20.” And, therefore, we also have an accumulated depreciation that starts to build in the balance sheet. This is also how we end up with a net asset value that’s constantly falling. In this example, if this company really wanted to grow, the problem that it would have is that this asset is basically worth nothing at the end of five years.

That’s just an accounting concept.

But in an economic sense, let’s say that they were right. The five years have passed, and the machine is dead. To make the machine last those five years and still produce at the same level, we would have to invest how much?

Twenty dollars! If we invested $20 in that machine every year, we would offset the amount that’s depreciating. And that’s the concept of depreciation.

We can look at that in more detail. But let’s look at the difference between the change in gross fixed assets and Capex.

Change in Gross Fixed Assets and Capex

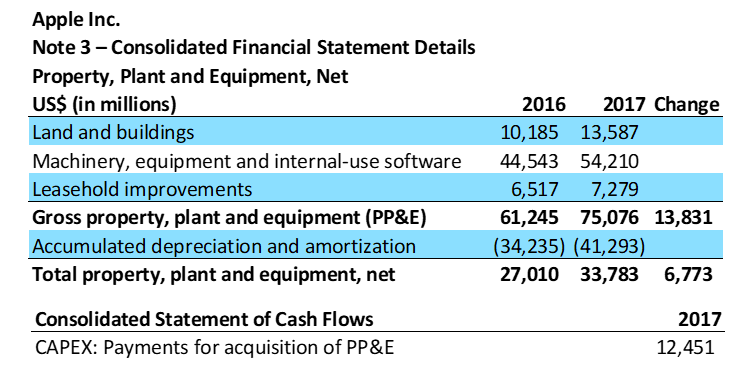

There are two Capex items in financial statements. Firstly, there is a change in gross fixed assets and secondly, there is the Capex line on the statement of cash flows. Let’s take a look at Apple Inc. as an example here:

As you can see, the 2017 change in gross fixed assets of US$13,831m does not match the Capex in the cash flow statement of US$12,451m. For various reasons, these items almost never perfectly match. In fact, I’ve never seen it match completely; and I have a database of almost every listed company in the world that we work on in my business as well as in the Valuation Master Class.

One simple reason is that, by definition, the statement of cash flows is only the cash that’s being spent currently.

Let me explain further. I went to visit a factory in Thailand once, and they showed me a lineup of these massive injection molding machines and the guy told me he got two-year credit terms for them, meaning no cash was spent on the machines in the first two years.

Let’s consider the case of Apple Inc. again. In 2017, the change in gross fixed assets was US$13,831 million (as per the table above). If we look at the 2017 change in gross fixed assets, it does not match the Capex item in the cash flow statement which is US$12,451 million. It’s close, but there are many, many complicated reasons why it’s still different and this is what it’s pertinent to remember. Both ways of looking at Capex have value.

When talking to company management, make sure you clarify which one they’re discussing. Ask, “Are we talking about the change in the gross fixed assets? Or are we talking about the Capex amount that’s going to be the cash amount reflected in the Capex?”

Capex Across Asia

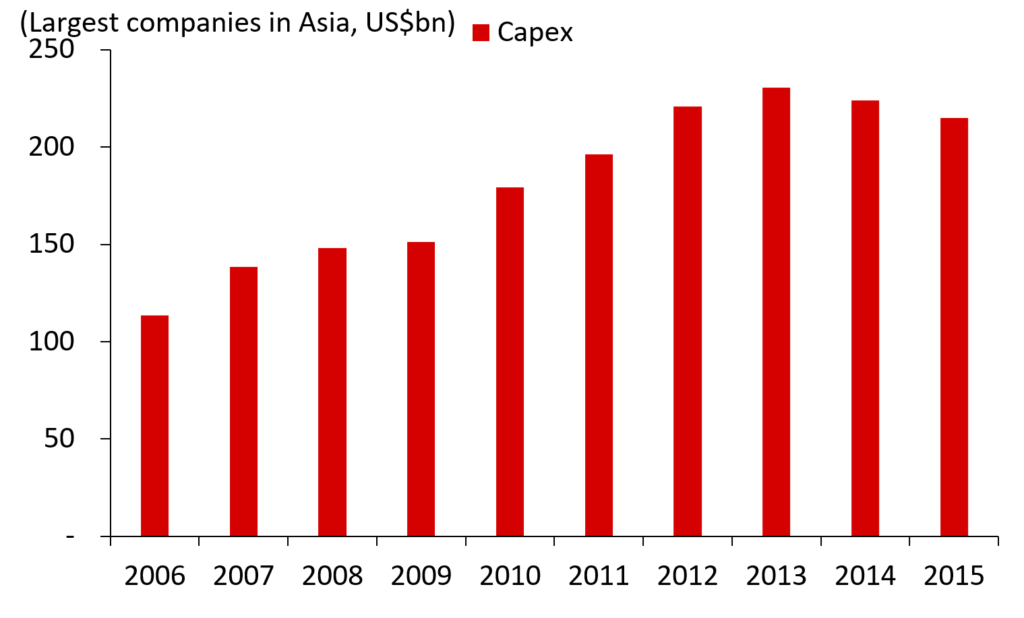

Let’s go back to my research on the 500 largest companies in Asia and their Capex spending in their cash flow statement. We can see that it started to come down in 2014 and 2015. But that’s the total amount of Capex that these companies are spending.

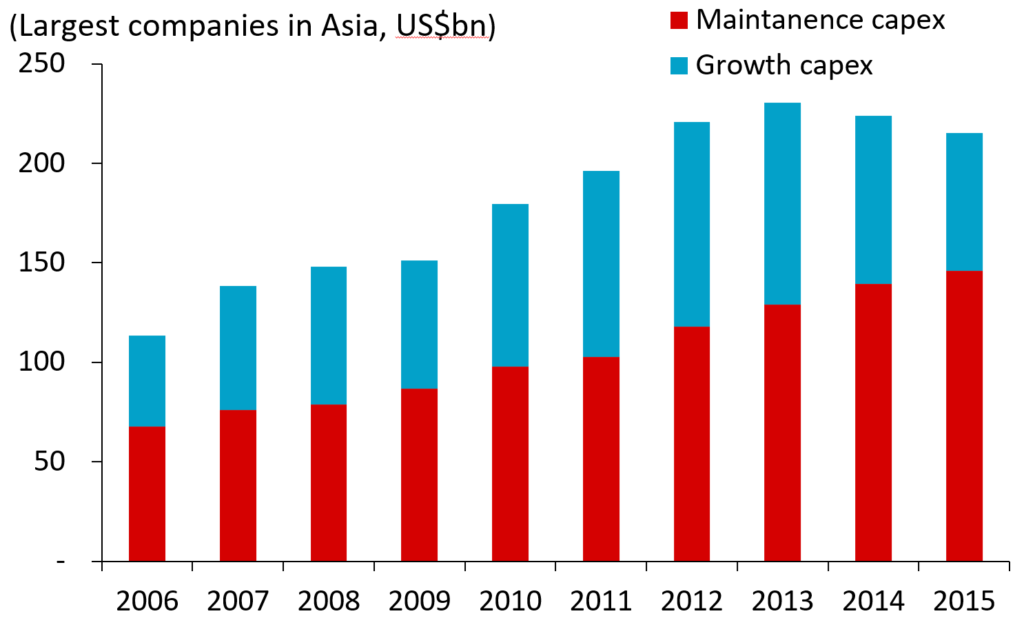

Now, let’s break that down into two parts. The first part is Maintenance Capex. We already looked at that a little bit earlier by looking at that depreciation of 20 and saying, “We’d have to invest 20 to offset the amount that it’s depreciating.” The second is Growth Capex.

Maintenance Capex is spending to keep an existing asset producing at the same level—older machines will require a lot of additional work in this area. When a company builds a new part onto a machine, that would be an addition to or a Maintenance Capex spending. There are short-term outgoings that will be required for machine upkeep, remember the can of oil from earlier, but these are expenses only.

Let’s look at Growth Capex. That’s when a company buys a new additional machine entirely, increasing its fixed assets for growth purposes.

Now, if that happens, what would a company do with the old machine? It can be kept or sold. So, let’s say that the new machine cost $200 million, and the old machine sells for $50 million. Therefore, the Net Capex amount for that year is $150 million.

In Maintenance Capex, the annual P&L depreciation charge is a good rough estimate of what must be spent to keep an asset up and running. You could dispute the accounting standard related to depreciation by saying, “Wait a minute, why would you depreciate something over five or ten years when you have a machine that’s been running for much longer than that?”

Herein lies the difference between economic value and accounting value. The accounting value of the machine that runs past its projected lifespan is now zero. But is the economic value the same? No. And as financial analysts, we are always looking at the economic value rather than the accounting value. Sometimes, we’ll also make adjustments to the accounting value to factor in the economic one.

For additional growth, a company needs to invest more than just Maintenance Capex. While Growth Capex has much more volatility, it is essentially the key to the future success of a company.

How to Avoid the Common Capex Mistakes?

Here are some general rules to help you avoid making this valuation mistake:

- For growth firms: The Capex should be more than the annual P&L depreciation charge, maybe around 150% of it

- For very high growth firms: The Capex should see more than 150% of depreciation

- For low or no growth firms: The Capex should be about equal to the annual depreciation charge

Mistake #4 Conclusion

- Always consider both Growth and Maintenance Capex

- Maintenance Capex should be roughly the same as depreciation

- The starting point for overall Capex forecasting is 100% of annual depreciation charge

- Additional Growth Capex depends on how fast you expect the firm to grow

Don’t forget to watch the video that accompanies this chapter:

Up next in the series, I discuss forecasting drastic changes in cash conversion cycle. Watch this space.

The Valuation Master Class provides you with the head start needed to achieve the equity analysis edge you need. Over the course of five modules, you will accumulate a portfolio of 56+ practical valuations on real-world companies. No other course provides the same opportunity to hone your equity analysis skills in the same way.