The Trade-off between Simplicity and Precision

In the trade-off between simplicity and precision, I choose simplicity.

I have more than 20 years of experience in the financial industry. First as an analyst, then as Head of Research. Over those decades, my thoughts on the trade-off between simplicity and precision have, to put it mildly, evolved.

These days I love to keep it simple! What follows is a story from my early years that demonstrates how the precision achieved by increased complexity, though tempting, may not end up leading to value added that is worth the cost.

During my first year on the job as an equity analyst, I recall my boss finishing a call with a client and asking me, “What is your earnings forecast for next year for Bangkok Bank?” I did what any new analyst would do: Tell him to wait and let me check my models.

Minutes turned to hours as I cranked through the massive Excel file I had on Bangkok Bank. I was terrified to give the wrong answer, so I kept looking at the financial statements from every angle. I felt like I needed more detail to adequately defend any answer I might give.

After a couple of hours, my boss stopped by and asked me for my answer. I replied, “I’m not ready yet.” Finally, the end of the day came and I went home, determined to wake up the next morning and settle on my answer.

The deeper I delved into the data, the more I felt there was still more I needed to consider. So I built a new section in my spreadsheet that analyzed yet another component of the company’s financial performance.

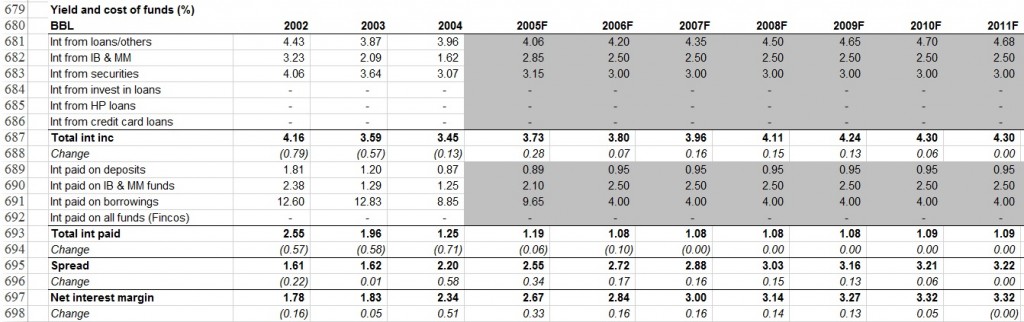

This model excerpt is actually a bit more recent but gives you an idea about how my models looked back then.

As my boss was on his way out for lunch, he strolled by and worriedly asked, “Have you got the answer?” I explained my new approach to him, told him my confidence level was rising, and that I would have a correct answer for him soon.

Near the end of the day, I went to my boss’s office.

“So, Stotz, what’s your conclusion?”

I told him about the hundreds of lines I added in my Excel model, and how I had looked at it from every conceivable angle. Clearly annoyed, he blurted out, “Just tell me your number!”

“9.73%.”

My boss smiled. “Good, because I told the client ‘About 10%’ yesterday.”

My boss had 20 years of experience. I had one.

He made a simple estimate. I made a complex one.

Mine could have even been more right, but the client never heard about the estimate I had worked so hard to perfect.

Now that I’m the one that has 20 years of experience, I see the trade-off between complexity and simplicity the way my boss saw it back then: Once you’ve sharpened a pencil so that it’s sharp enough to write with, stop. You can keep trying to perfect that pencil point all day long, and while you waste time doing so, someone else is already writing.

Specific to this example, it’s worth noting that the forecasting ability of financial analysts is actually worse than a coin toss. This doesn’t mean that I don’t forecast, it just means I understand the law of diminishing returns as it applies to time management: After a certain point, additional hours spent fine-tuning an already-solid estimate would be more productively spent elsewhere.

DISCLAIMER: This content is for information purposes only. It is not intended to be investment advice. Readers should not consider statements made by the author(s) as formal recommendations and should consult their financial advisor before making any investment decisions. While the information provided is believed to be accurate, it may include errors or inaccuracies. The author(s) cannot be held liable for any actions taken as a result of reading this article.