Peaking US Net Margin and the Hidden Effect of Fed’s Policy

In February 2018, we posted a chart of the day titled Fed’s Tightening Has Not yet Killed This Bull. In October 2018, we published a chart of the day titled Continued Uptrend in Net Margin, but Nearing Peak in Developed Markets highlighting the risk that the net margin in Developed markets, driven by US tax cuts, was nearing its peak.

What follows below are some charts presented on 18 December 2018 in our Global FVMR strategy which give some updates with regards to US net margin and the hidden effect of Fed’s low-interest rate policy. If you’re subscribing to our newsletter, you saw a few of these charts a couple of weeks ago.

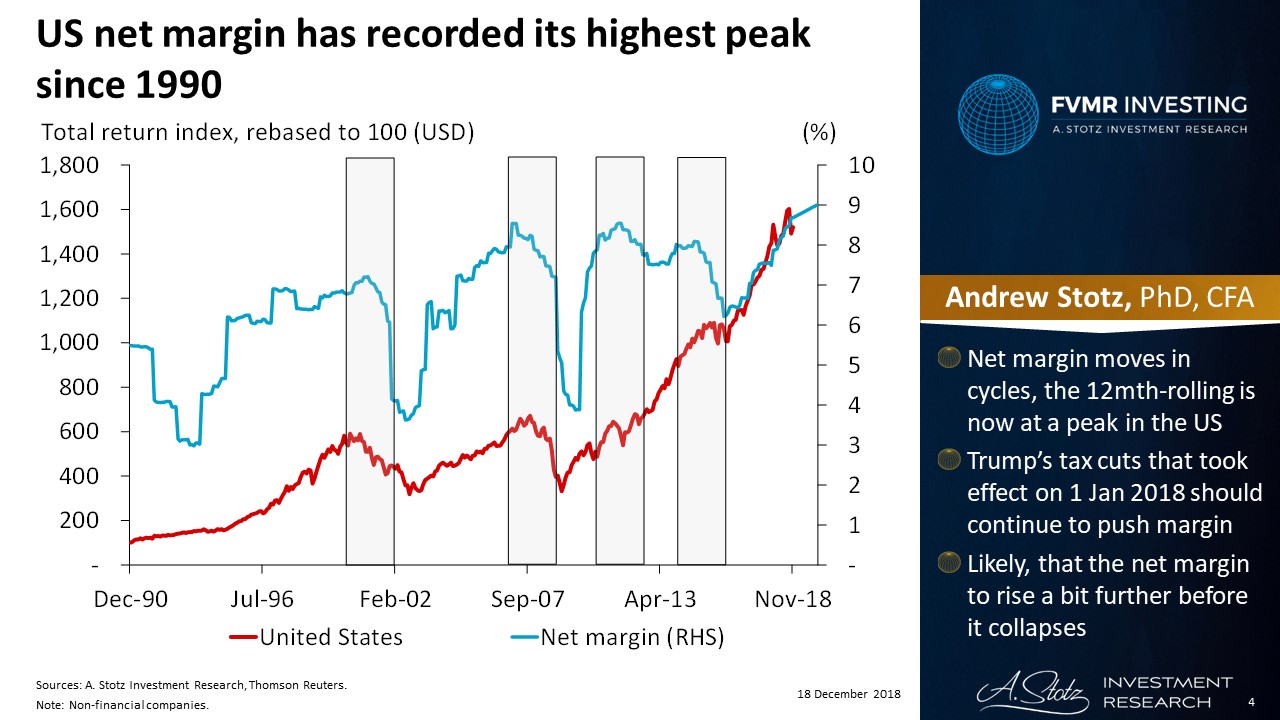

US net margin has recorded its highest peak since 1990

- Net margin moves in cycles, the 12month-rolling is now at a peak in the US

- Trump’s tax cuts that took effect on 1 January 2018 should continue to push margin

- Likely, that the net margin rises a bit further before it collapses

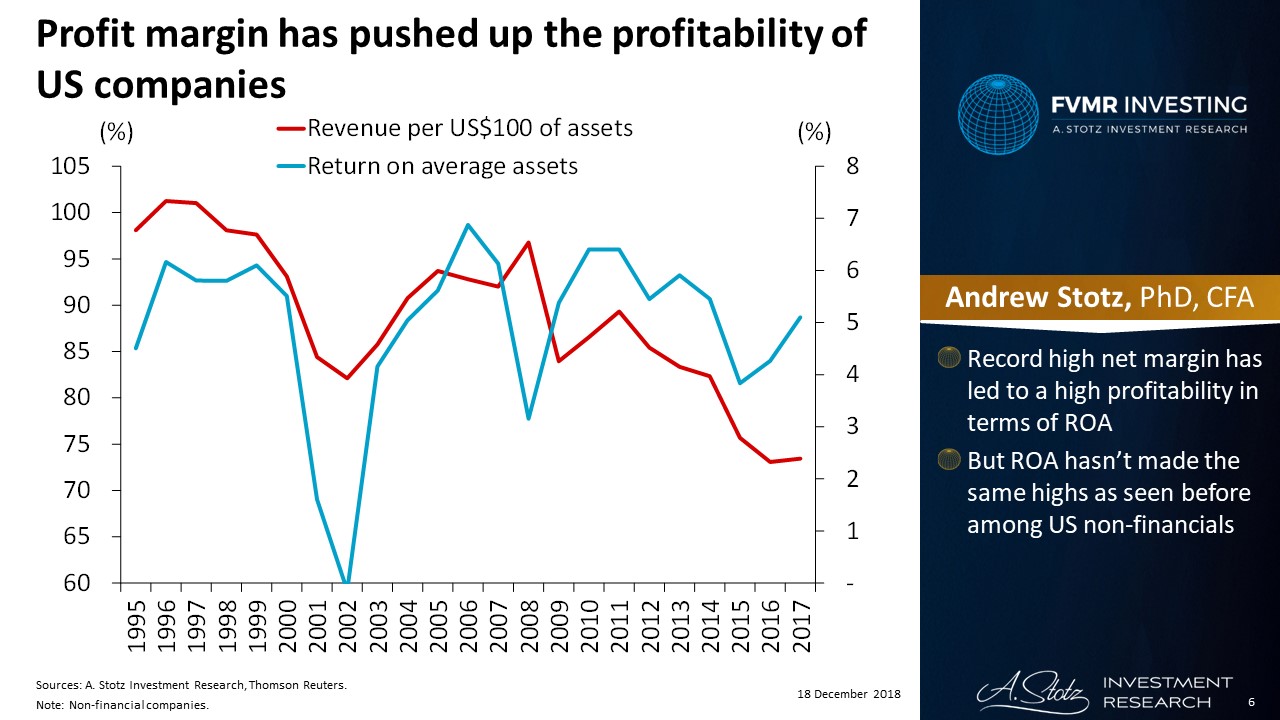

Profit margin has pushed up the profitability of US companies

- Record high net margin has led to high profitability in terms of return on assets (ROA)

- But ROA hasn’t made the same highs as seen before among US non-financials

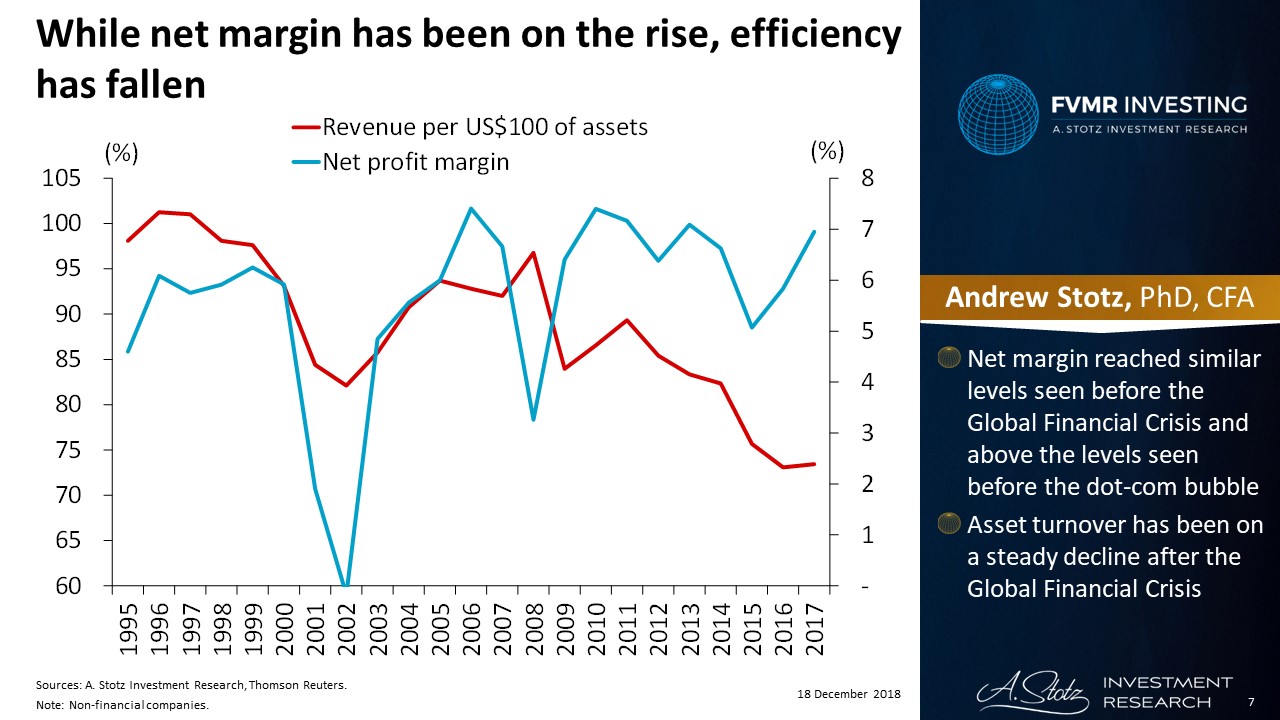

While net margin has been on the rise, efficiency has fallen

- Net margin reached similar levels seen before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and above the levels seen before the dot-com bubble

- Asset turnover has been on a steady decline after the GFC

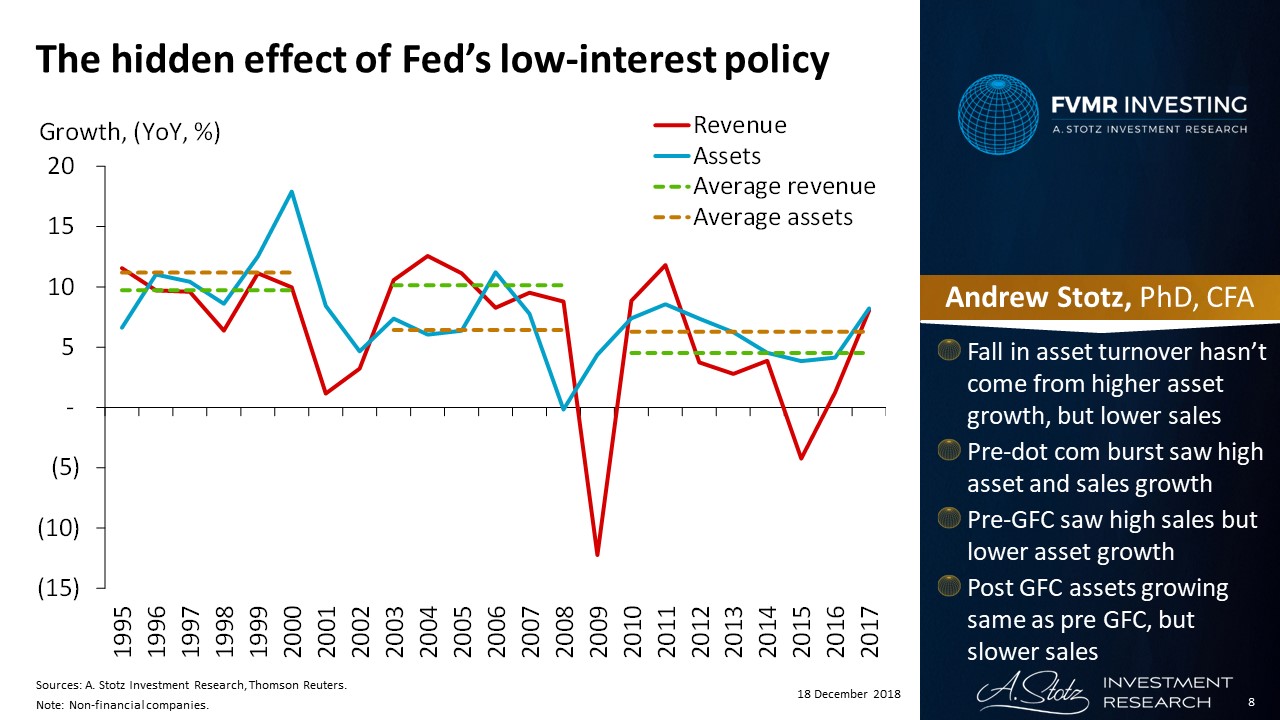

The hidden effect of Fed’s low-interest policy

- Fall in asset turnover hasn’t come from higher asset growth, but lower sales

- Pre-dot com burst saw high asset and sales growth

- Pre-GFC saw high sales but lower asset growth

- Post GFC assets growing same as pre-GFC, but slower sales

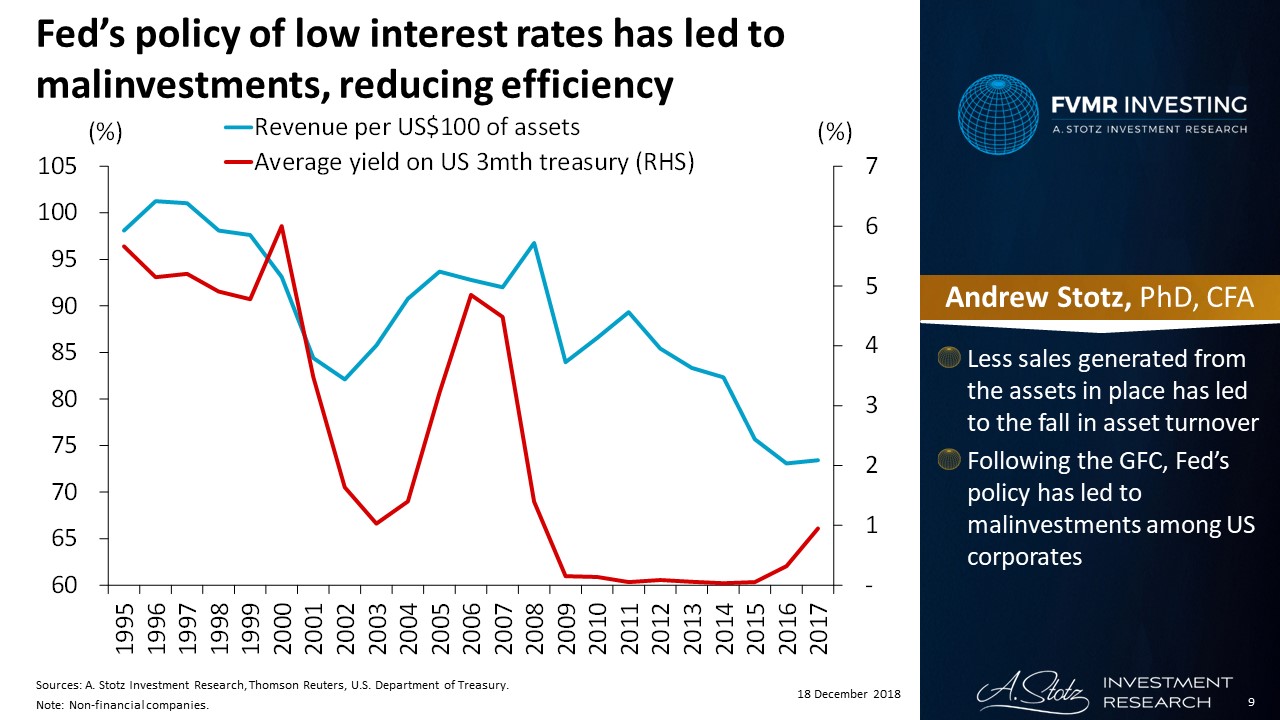

Fed’s policy of low interest rates has led to malinvestments, reducing efficiency

- Less sales generated from the assets in place has led to the fall in asset turnover

- Following the GFC, Fed’s policy has led to malinvestments among US corporates

On malinvestments in Austrian economics

The Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises laid out the relationship between cheap credit and malinvestment in his book Human Action, published in German in 1940 and in English in 1949.

Austrian economists see swings in the business cycle as naturally occurring and something that is needed to clear out weak competitors. Like the way a forest fire clears overgrowth, making way for new plants.

They argue that central banks amplify the economic cycles by setting artificially low-interest rates during bust periods which artificially stimulates borrowing from the banks.

But since the economy is facing oversupply due to the prior boom, this availability of credit encourages companies to invest in less profitable projects, which Austrian economists call “malinvestment.”

DISCLAIMER: This content is for information purposes only. It is not intended to be investment advice. Readers should not consider statements made by the author(s) as formal recommendations and should consult their financial advisor before making any investment decisions. While the information provided is believed to be accurate, it may include errors or inaccuracies. The author(s) cannot be held liable for any actions taken as a result of reading this article.